With the NDP offering a national child care program – capping fees at $15 a day – in this election, quality, affordable child care has become a hot issue on the federal campaign trail.

It’s also an issue that will likely resonate with many Ontarians who are concerned about high child care fees and stagnant incomes.

This post focuses on another good reason to invest in high quality, universal child care in Canada: improvements in women’s labour force participation.

Focusing on the Quebec experience – where child care was introduced in 1998 for an affordable $5 a day[1] – Fortin, Godbount and St-Cerny found that the introduction of universal child care boosted women’s employment by 9.3 percentage points by 2006.[2]

That represents a 12 percentage point increase in the employment rate of mothers with children under six and a seven percentage point increase in the employment rate of mothers with children aged six to 14.

This translates into an additional 69,700 mothers working than would have been working if the program had not been implemented.

The benefits of an affordable child care program were profound. The program was found to have the direct effect of increasing Quebec’s GDP by 1.7%, increasing total government revenue by $2.2 billion in 2008 and reducing total social assistance benefits paid by $116 million.

In short, as a result of the increased employment rate of mothers, the Quebec child care program more than paid for itself in returns to all levels of government.

What might the impact of universal child care be in Ontario?

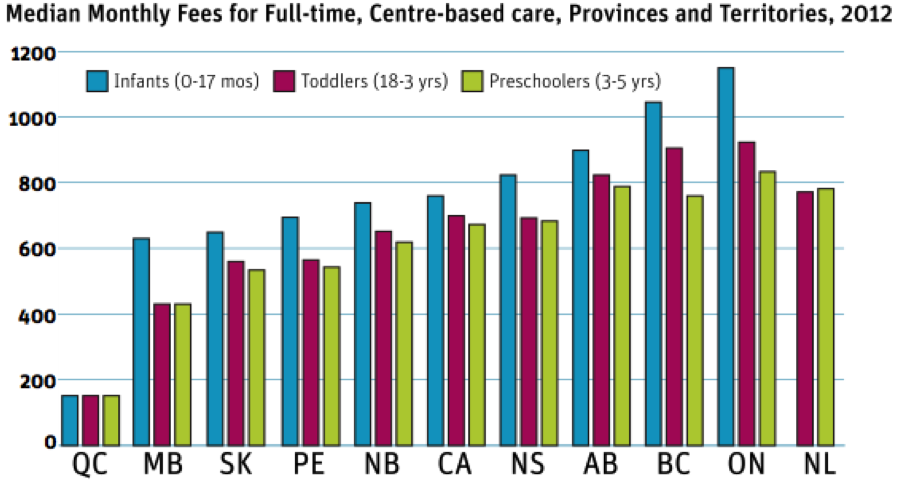

Ontario is currently home to the highest median parent fees in Canada. In the City of Toronto, child care is the biggest expense that families with young children face, on average.

Ontario does fund a subsidy program for low-income families, but the wait lists are long. In Toronto, the child care subsidy wait list averaged just over 17,000 in the first three months of 2015.

Where child care is concerned, Ontario is home to seven of the 10 least affordable cities in Canada, according to a child care affordability index constructed by CCPA Senior Economist David Macdonald and CCPA Research Associate Martha Friendly last year.

Would more Ontario women joining the labour force be enough to mimic the experience in Quebec?

Using Fortin’s findings as a guide, we can provide some estimates of what the results might look like in Ontario. I took Fortin et al.’s calculation for Quebec and created a comparable table for Ontario with more recent figures. These are presented below:

Such an investment in affordable child care in Ontario could increase employment income by about 1.8 per cent, leading to a direct and indirect increase in GDP of $12.5 billion (Ontario Finance, 2014).

A child care fuelled increase in the employment rate could contribute to GDP in static and dynamic ways. More women would be earning an income in the work force. When that income is spent in the local economy, businesses gain more and/or repeat clients and sales, and they are able to employ more workers who, in turn, have and income to spend in the local economy.

When employed, mothers will also pay income tax and reduce reliance on government supports and transfers, both of which have an impact on government budgets and overall expenditures.

As a result, federal and provincial and governments could expect to see increased revenues to offset the cost of offering more affordable child care spaces to parents.

The potential increase in provincial government revenue could amount to $1.7 billion a year and the total potential increase in revenue for all levels of government (ie, including the feds) could reach $5 billion.[7] Just another reason why Ontario needs a committed federal partner moving forward.

This increased revenue would result from the increased income tax and sales tax revenue that more working families would pay because they would have more money to spend.

The lesson from Quebec shows another added benefit of investing in an affordable child care program: fewer families - particularly single parent families - received social assistance.

Any child care program should focus on quality, as well as expanding the number of publicly funded, regulated child care spaces available to parents. It is not enough to simply make existing spaces cheaper; the focus must also be on keeping the quality high as well.

Research confirms that children in high quality child care benefits all children, particularly those living in low-income families. This can't be said when the focus is placed on price alone.

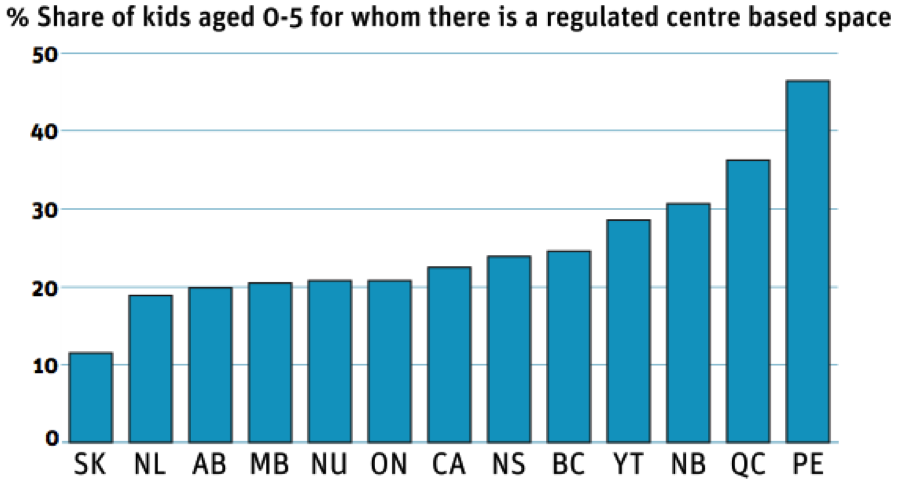

In Quebec that number is 36% and in PEI it climbs to 47%. Clearly, there's room for improvement in Canada's largest province. A federal-provincial initiative to expand the share of affordable, quality child care spaces in Ontario could be a win-win.

The experience in Quebec shows that it's a sound public investment that's well worth any government's while.

Kaylie Tiessen is an economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives' Ontario Office.