EXCERPTS

The Issue:

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly affected American families and children in many ways, including through rupture in the nature of their primary care and school settings. Even one year into the pandemic, children have to contend with unpredictable disruptions to their learning that were unheard of before the pandemic began.

Sources of disruption range from internet and software failures to sudden classroom closures, meaning that learning mode—whether remote, in person, or hybrid—cannot fully insulate families from these disruptions.

We followed families of hourly service workers with young children as the pandemic unfolded, and discovered that a large share of the families participating in our study experienced unpredictability and disruptions on any given day. Moreover, we found that on days when care or school did not go as planned, family well-being dropped markedly.

Frequent, unexpected disruptions in the care and schooling of children have significantly contributed to the daily burden for families during COVID.

The Facts:

A daily survey of low-wage service workers with young children, which started in late 2019, provides a window into how the pandemic impacted their day-to-day lives. We recruited a representative sample of hourly service workers in retail, food service, and hotel establishments who had young children in Philadelphia during late summer and fall of 2019 to understand the effects of parents’ unstable work schedules on family well-being.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the original goals of the study. However, we continued to follow this sample of highly policy-relevant families throughout the pandemic. Because the children were between 3 and 8 years old in the fall of 2020, they could not be left alone while parents worked, and parents therefore faced additional challenges balancing their work and family responsibilities. Most of the families in our sample were not able to work from home.

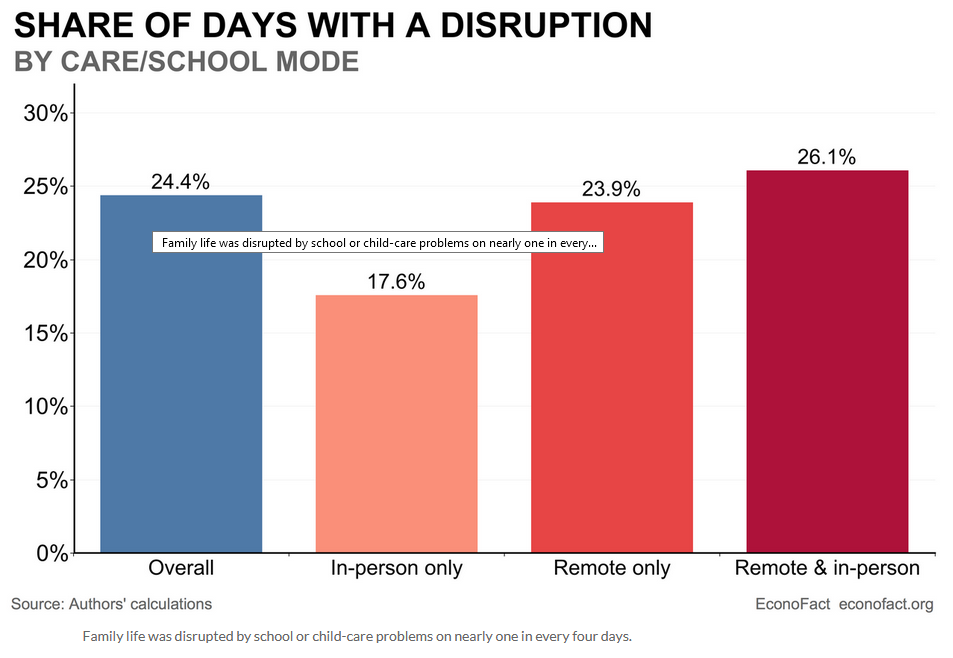

Throughout the first half of the 2020-2021 school year, the families in our sample faced frequent disruptions to their children’s care and school arrangements. Each respondent in our study answered the following question every day for 30 days: “Did your child(ren)’s child care/school go smoothly today—happened on schedule, internet worked if needed, etc.?” Those who checked “not at all”, “somewhat” or “mostly” were categorized as having experienced disruptions. The share of days on which school or care did not go as planned was strikingly high, at nearly a quarter of days (see chart above). The vast majority of families, 77%, experienced at least one disruption in the fall.

While daily disruptions were frequent overall, they were significantly more common for families using only remote learning (23.9% of days) than for those using only in-person school/care (17.6%), with the highest rates for those using both modes (26.1%), likely because those families faced disruptions from multiple sources.

We used a simplified approach so as to allow us to have a large sample answer this question daily. However, this meant that we were not able to ask detailed follow-up questions, so we are not able to parse out from this data whether a given disruption was due to internet failure, COVID-19 cases, or some other specific source.

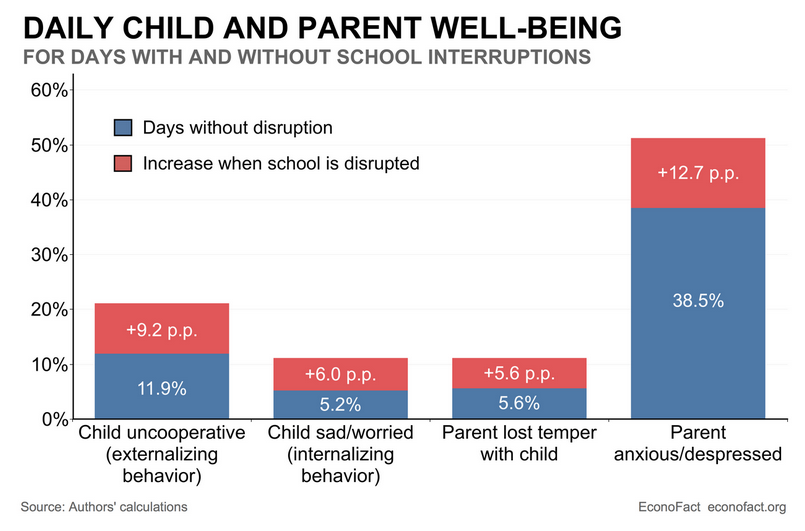

Both children and parents had more mood or behavior problems when the kids’ day was disrupted.

Children fare worse when care or school is disrupted. On days when children’s care or school did not go as planned, the share of parents who said that their children were uncooperative “some or a lot today” was 21.1%, a striking and significant increase of 9.2 percentage points from a base rate of 11.9% on days without disruption (see chart). The pattern was similar for effects on parents reporting that children appeared to be sad or worried “some or a lot today,” with a significant overall increase of 6.0 percentage points (more than doubling the base rate of 5.2% on days without disruption). Disruptions led to increased uncooperativeness and sadness whether children were in remote learning or in-person care or school, but the increase was somewhat smaller for children in remote learning compared to the increase in uncooperativeness and sadness that children attending in person experienced when there was a disruption.

Parents’ mood and behavior have experienced measurable declines with the pandemic and show further deterioration when care or school is disrupted. Parents in our sample reported very high levels of anxiety and depression, with 38.5% of parents reporting these symptoms on any given day. This finding, while extremely high, is in accordance with findings of broader national surveys: The percentage of adults reporting symptoms of anxiety or depression averaged 38.1% in the Household Pulse surveys conducted from April 2020 through February 2021. In comparison, about 11% of U.S. adults reported experiencing these symptoms from January to June 2019 in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) survey conducted in 2019 using similar questions, according to a recent report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Learning disruptions strongly affected daily parent mood above and beyond these elevated levels. The share of parents in our sample who said they felt fretful, angry, irritable, anxious, or depressed that day increased by a significant 12.7 percentage point. Perhaps not surprisingly given effects on mood, parents were significantly more likely to lose their temper with their child on a day with a disruption; the overall increase was 5.6 percentage points, double the base rate of 5.6% on days without disruptions. These increases were consistent for parents with children learning in-person or remotely.

Differences by race and ethnicity are significant, while patterns are strikingly uniform across groups. Although the debate around whether or not schools should be reopened during the pandemic has often invoked the needs of families of color, little research has actually provided empirical evidence of the experiences of different modes of learning among families from different racial and ethnic groups, particularly within income and occupation strata.

Within our sample, Hispanic parents reported the highest incidence and frequency of disruption and of difficulty supporting learning, while non-Hispanic Black parents’ reports were lower and non-Hispanic white parents’ reports were in between. For all race and ethnic groups, the frequency of daily disruptions to learning was higher in remote than in in-person school or care, but the differences were significantly larger for Hispanics (40% more frequent disruptions in remote than in in-person learning) and non-Hispanic Blacks (60% more frequent) than for non-Hispanic whites (29% more frequent).

By contrast, the effects of daily disruptions on child well-being were larger for non-Hispanic whites than for families of color (the difference between non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics was significant for child sadness or worry, while the difference between non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic Blacks was significant for uncooperativeness). Similarly, effects of disruption on temper loss were larger for non-Hispanic white parents than for parents of color (the difference with non-Hispanic Black parents was statistically significant).

At the same time, for all of these child and parenting outcomes, effects were substantial in size and statistically significant for all three racial and ethnic groups. On parent well-being, we observed large and significant effects of disruption for all race and ethnic groups, with no statistically significant differences in estimates between groups.

What this Means:

There has been little evidence about the experiences of disruptions to children’s care and school arrangements as the pandemic has persisted through the 2020-2021 school year, nor about the effects of those disruptions on child and family well-being. By using innovative daily survey data gathered in the fall of 2020 from a representative sample of hourly service workers with young children, we are able to shed light on the frequency of disruptions to school and care, and the consequences of those disruptions for child and parent mental health, among a group of families with significant but common vulnerabilities.

While previous work had documented that universal, short closures (such as snow days) had few effects on children, we document that frequent, unexpected disruptions in care and learning have significantly contributed to the daily burden for families during the pandemic.

Policies to increase the safety, accessibility, and predictability of in-person learning hold promise to reduce disruptions. Moreover, as school districts prepare for a new school year in which many plan to continue offering remote options, additional support and resources for families in remote modes may be needed to stabilize their day-to-day experiences.

Finally, this research provides further evidence on, as well as identifying additional sources of, emotional distress among children that schools and other child-serving organizations will need to address as they try to repair the damage incurred in the pandemic.

Support for this research was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (Grant #1R21HD100893-01), the National Science Foundation (Award # SES-1921190), the Russell Sage Foundation (Grant #1811-10382) and Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Excellent project support was provided by Jennifer Copeland.

This commentary was originally published by Econofact—Impact of Disruptions to Schooling and Childcare During the Pandemic.